Effective communication and teamwork is essential for the delivery of high quality, safe patient care.

Failures to communicate are the leading cause of inadvertent patient harm.

Closed-loop communication (CLC) is essential for safety and precision in healthcare, particularly during complex surgeries involving intraoperative neuromonitoring (IONM). The neuromonitoring clinician cannot effectively do their primary function without clearly and confidently communicating baseline data, early changes, wave loss, or stimulation results.

(I would say in the context of an “early change”, anything that is an immediately noticeable trace-to-trace difference that I can’t attribute to a technical or anesthetic factor warrants at least a brief notification.)

In surgical environments, situational awareness is vital. CLC enhances this awareness by ensuring that all information is not only shared but acknowledged and confirmed by the appropriate team members.

Phrases like “Dr, I have a complete loss of right leg and foot MEP responses” or “Responses have returned after increasing the MAP” must be acknowledged aloud by the surgeon or anesthesiologist to confirm shared understanding and coordinated action.

Teams should use effective tools and structured communication behaviors, such as the SBAR technique (Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation). For example:

- S: “We’ve lost MEPs in the left lower extremity.”

- B: “Signals were stable prior to osteotomy.”

- A: “This may indicate some level of spinal cord compromise.”

- R: “Recommend surgical pause, increase in MAP, and re-testing after a few minutes.”

Using critical language – clear, standardized phrases that denote urgency or required action – also supports rapid response. Terms like “Signal loss,” or “Absent after…,” convey priority issues that must be addressed without delay. Hinting and hoping that you have been heard is fraught with hazard.

There is a hierarchy in medicine, and while it may be difficult to speak up with concerns due to certain power structure, cultural norms, or uncertainty, the ability to get everyone to stop and listen is essential for safe care. The reliability of IONM is threatened when the clinician’s role is neglected, and the decision to change course of a surgery relies heavily upon the communicator.

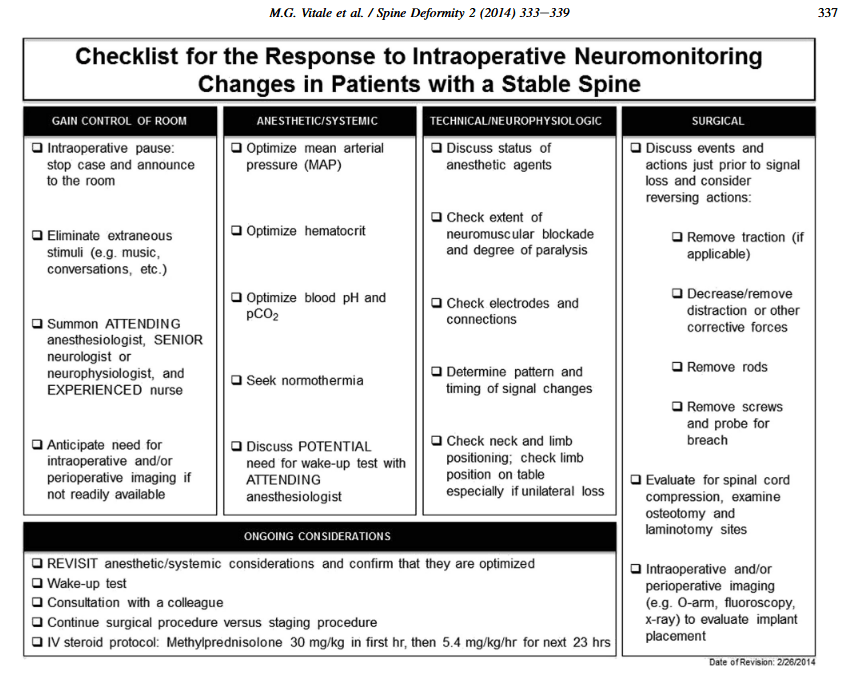

Checklists can be extremely useful to ease cognitive burden when faced with potential significant changes. And while there’s no substitute for being having situational awareness, we must all be cognizant and anticipate “the next steps” when dealing with waveform loss. See the following from Vitale 2014, a classic in the IONM world.

As neuromonitoring clinicians, we must overcome the heavy cognitive bias of the surgeon when there is a change. They will (understandably) want to see their carefully planned procedure through to the end, and experience with changes and patients waking with no or extremely minimal deficit can prohibit taking action when there is potentially serious change.

Maintaining team alignment through frequent communication about patient history, surgical milestones, and frequency of testing ensures the neuromonitoring clinician is integrated – not isolated – in the care process.

Ultimately, we must all be accountable for the patient. Every team members commitment to structured, reliable communication, shared awareness, and mutual respect ensures the best possible outcome for the patient.

For more reading, I suggest:

Dormans JP: Establishing a standard of care for neuromonitoring during spinal deformity surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 35:2180–2185, 2010

Leonard M, Graham S, Bonacum D: The human factor: the critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. Qual Saf Health Care; 13 (Suppl 1):i85-i90, 2004

Vitale MG, Skaggs DL, Pace GI, Wright ML, Matsumoto H, Anderson RC, et al: Best practices in intraoperative neuromonitoring in spine deformity surgery: development of an intraoperative checklist to optimize response. Spine Deform 2:333–339, 2014

Leave a comment