This case describes three separate interventions for positional lower extremity SSEP changes over the course of the first half of a L2-4 PTP with varying degrees of improvement in SSEP data. Interestingly, the evoked potential of most concern (left saphenous) remained the most stable compared to other waveforms throughout the procedure.

Most of these changes occur either before retractors are placed, or on the contralateral side of interbody placement (working from left side). We show that it is possible to develop SSEP changes via overtightening of pelvic hip pads + strap.

Patient was a 77 year old male with a history of low back and left-sided leg pain into his knee. He is 180cm tall and weighs 103kg. He denied any focal weakness. He has a history of previous left knee arthritis and replacement, coronary artery disease, and bladder cancer. He has lumbar stenosis, spondylosis with radiculopathy, and lumbar spondylolisthesis at the L2-4 levels.

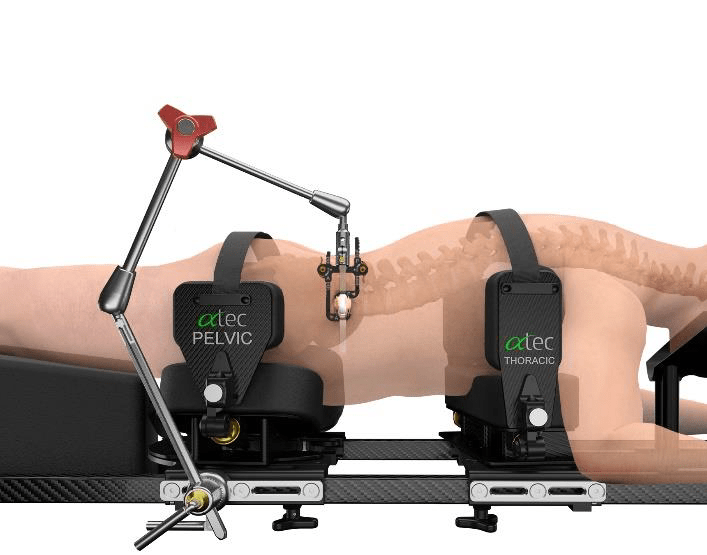

Patient was positioned in the standard position for the prone transpsoas (PTP) approach (ATEC). Patient was turned on a Jackson table with chest and hip pads placed in the traditional fashion. Hip pads were secured with strap across buttocks.

Neuromonitoring included Somatosensory Evoked Potentials (SSEP) of the Posterior Tibial (standard ankle stimulation) and Saphenous (proximal- needle electrodes placed in thigh) Nerves and lower extremity electromyography (EMG), utilizing needle electrodes for vastus medialis & lateralis, biceps femoris, and anterior tibialis muscles (Standard ATEC SafeOp PTP Test). TOF was placed at the standard left peroneal nerve and was 4/4 throughout nerve & screw stimulation. All nerve stimulation trials were >10mA and all screws stimulated at >20mA.

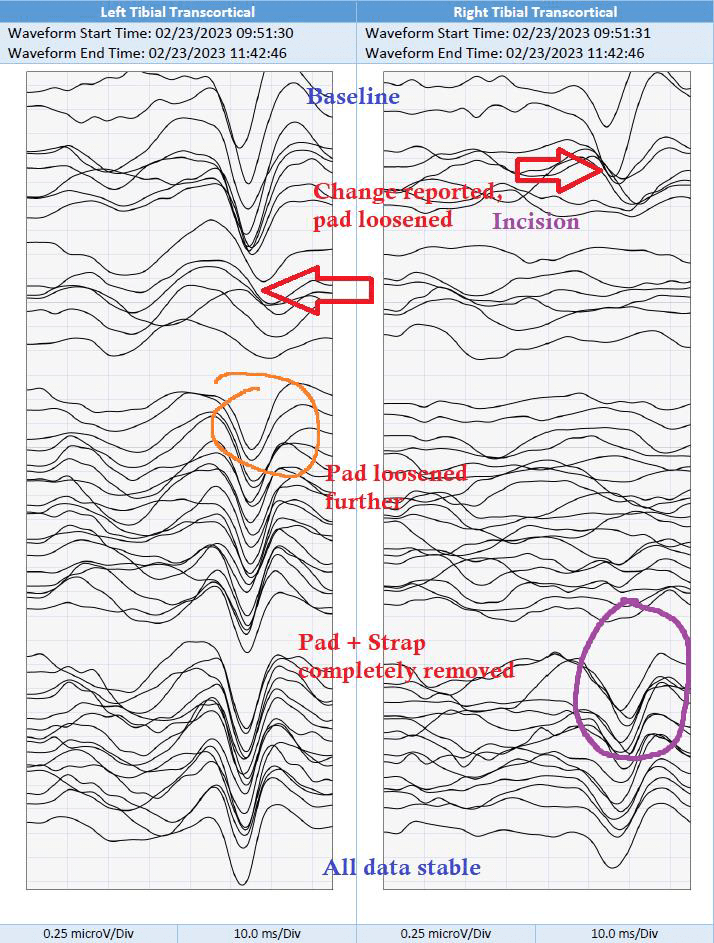

Shortly after initial traces and baselines – and just around incision – a change in right tibial (Cortical + Transcortical) SSEPs were noted and reported (red arrows). Technical factors such as stimulation failure were ruled out as well as anesthetic factors, which had started at 1.5% and then 2.5% Sevofluorane during positioning, were mitigated by utilizing a total intravenous anesthetic (TIVA). MAP was maintained in the high 70s/low 80s. Propofol and remifentanil were maintained at 100mcg/kg/min and 0.10mcg/kg/min respectively throughout the remainder of the procedure. Left tibial SEPs and bilateral saphenous transcortical responses began to decrease in amplitude and demonstrate morphological changes while these changes were being discussed and troubleshooted.

The hip pad was not readily viewable due to c-arm telescope blocking, so it was unclear what could have been affecting positioning. Once c-arm was moved, the apparent right pelvic pad was loosened slightly to maintain current desirable positioning. A slight improvement in Right Saphenous and Left Tibial SEP was noted (orange circle) but further deterioration of bilateral Tibial SEPs persisted.

Right tibial SEPs (Cortical + Transcortical) at this point were nearly abolished. The right pelvic pad was loosened further with moderate recovery of the bilateral saphenous SEPs (green circle).

Finally, the strap was cut and the pelvic pad was completely removed which allowed for a very rapid return of tibial cortical and transcortical responses (purple circle). These responses remained stable throughout the remainder of the procedure with no additional alerts. The patient went home the following day with no apparent deficit.

Caution and care should be taken when placing and securing pelvic hip pads and straps. Improper positioning and overtightening of pads can lead to nerve fiber ischemia and peripheral nerve injury.

Neuromonitoring must begin early and performed continuously throughout all surgical stages to identify changes in IONM data.

All data remained stable up and including to the end of monitoring.