The femoral nerve is the largest branch of the lumbar plexus. It originates from posterior L2 divisions to L4, and innervates the surfaces of the medial and anterior thigh. The saphenous nerve is monitored as the largest cutaneous branch of the femoral nerve to reflect femoral nerve sensory function during indicated procedures. For the lateral lumbar and eXtreme lateral interbody fusion (LLIF and XLIF) procedures, which are mostly performed between the L2-L5 levels, this main branch is mostly at risk by way of retraction systems in situ. This case presents an example of saphenous nerve SSEP changes with relatively stable tibial nerve SSEPs, further reinforcing the importance of saphenous nerve monitoring during lateral procedures.

This patient was a 45-year old female, presenting with complaints of excruciating lower back and left-sided leg pain with associated numbness through her hip and into her foot. She was also beginning to experience these symptoms on the right. She had no weakness. She states she had no history of diabetes, hypertension, seizure, or stroke. Her prior surgical history included a lumbar fusion at L4-5 and a cervical fusion.

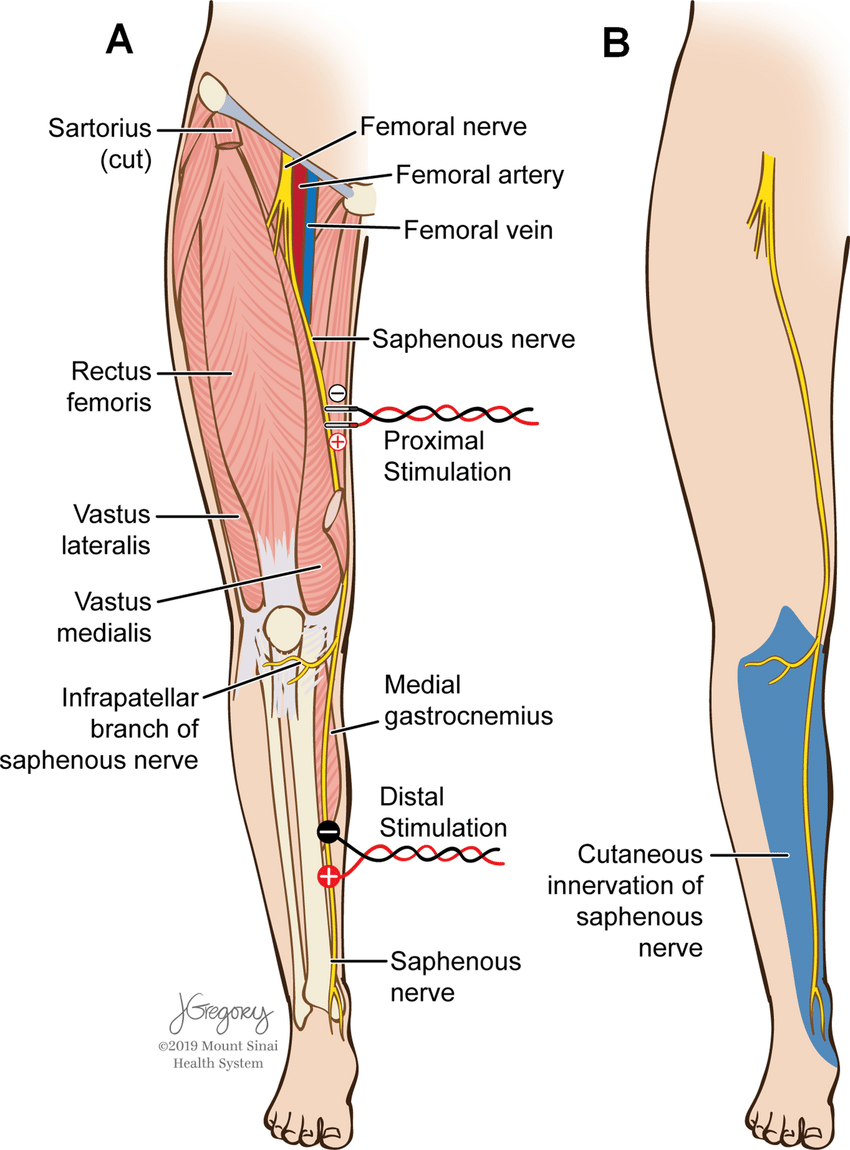

She was positioned in the lateral decubitus position with her left side up and knees bent towards her chest. Tape was wrapped around the hips, just above the knee, and across the lower legs to keep her in place on the bed. Pillows were placed between the knees. Anesthetic protocol included a total intravenous method, utilizing between 100- 150mcg/kg/min of propofol and a steady 0.30mcg/kg/min of remifentanil. Surgeon requested SSEP monitoring (Saphenous + Posterior Tibial + Ulnar) with NuVasive EMG for dilator / nerve stimulation. Needle electrodes were placed in the standard placements for PTN, SN (Fig 1), & UN stimulation with additional needles behind the popliteal fossa and sticky pads over the femoral nerve as back-up for saphenous nerve.

nerve SSEPs (figure from Silverstein et al. 2015)

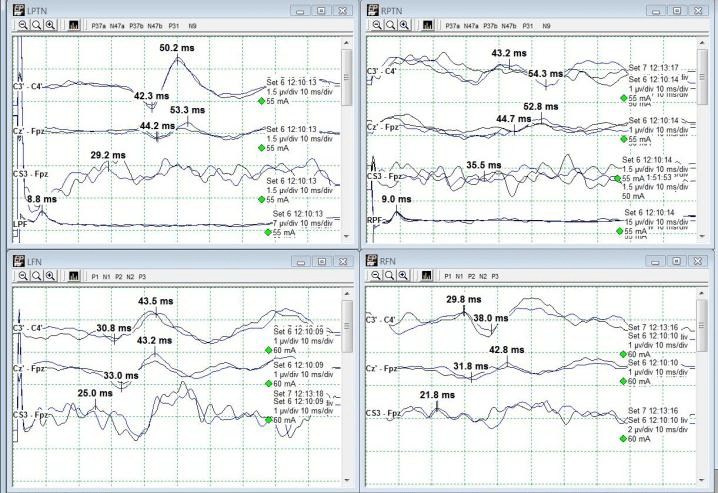

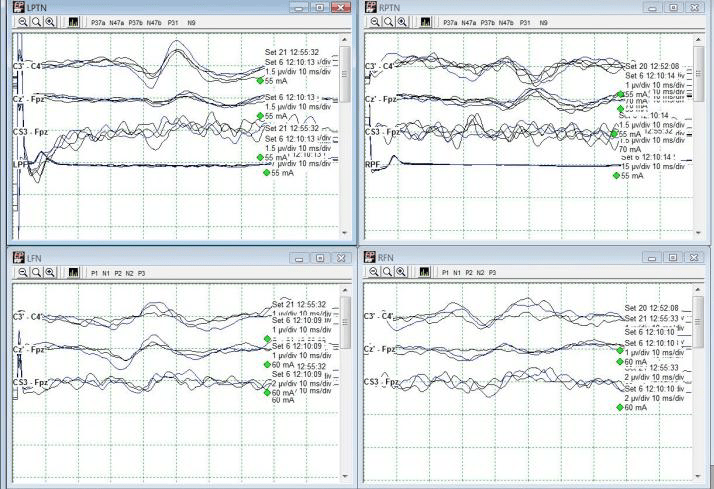

Baseline SSEPs were monitorable from all extremities except for RPTN, which was just barely marginally present. (Fig 2). Initial RPTN SSEPs were monitorable but quickly appeared to wash out following additional traces. PTN SSEPs were stimulated at 60mA 0.5ms 2.09Hz, SN SSEPs at 70mA 0.5ms 2.09Hz, and UN SSEPs at 30mA 0.3ms 2.09Hz. PTN + SN SSEPs were interleaved on the same timeline to more quickly acquire lower extremity data.

A change in the LSN SSEPs was reported almost immediately after setting baselines and prior to any implant sizing or placement (Fig 3). Some decompression work had begun but it was believed based on stimulation trials that the surgeon was well away from any significant nerve roots or groups. No problems in SSEP stimulation delivery were apparent based on movement during stimulation in all 4 extremities.

The recommendation therefore was made to maintain an elevated blood pressure (declined due to surgeon preference for lower mean blood pressure for less bleeding) and to remove any distraction down at the legs. The surgeon declined this at the time as well, stating that he had a good deal of retraction in place and that it would interfere with surgical maneuvers. For the time being, the legs were only gently moved around and shaken to attempt to restore some blood flow to the legs.

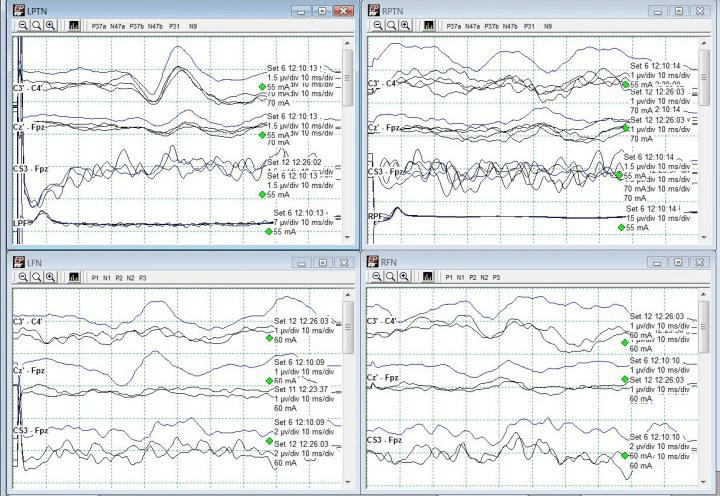

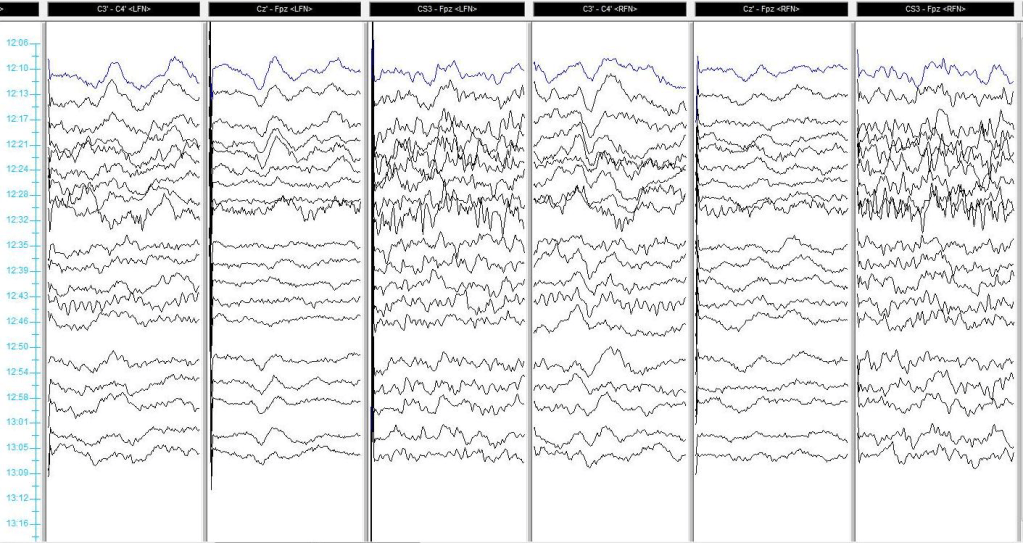

Immediately after instrumentation was in place, the tape across the hip, knee, and foot was cut away and removed. The left leg was lifted off the right and set back into its original position, only without tape. Within one data set, LSN SSEPs were within baseline parameters (from 90%+ reduced) and Right PTN SSEPs were much more reliable in cortical channels (Fig 4). Some improvement was seen in LSN subcortical responses as well.

The patient was then flipped to prone for posterior instrumentation with no significant events. She woke up with no additional deficits, and not much psoas pain which is very common following lateral spine surgeries. Because the actual data changes occurred in only LSN SSEPs, this case demonstrates the usefulness of saphenous and/or femoral nerve SSEPs in not only directly assessing L2-L4 nerve root function, but also as a reflection of possible malpositioning during lateral spine surgery.

Monitoring PTN + SN/FN SSEPs on the same timeline can be helpful to evaluate most at-risk sensory pathways simultaneously. Positioning effects can occur prior to any monitoring and must therefore be approached quickly in the absence of monitorable baselines in patients with no pre-operative deficits.

For more reading, please see the always-fantastic Dr. Silverstein’s article:

Silverstein J, Mermelstein L, DeWal H, Basra S. Saphenous nerve somatosensory evoked potentials: a novel technique to monitor the femoral nerve during transpsoas lumbar lateral interbody fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014 Jul 1;39(15):1254-60. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000357. PMID: 24732850.