Introduction

“If you wish to monitor the nervous system, you must first invent the universe.”

-Shamelessly stolen and modified from Carl Sagan

Intraoperative neuromonitoring relies heavily on the principles of electronics to record and interpret the electrical activity of the nervous system during surgery. Whether we’re evoking responses with electrical stimuli or recording neural signals, a firm grasp of basic electronics helps us understand both the biological phenomena and the technical challenges we may face in the operating room. It is imperative to have a firm grasp on this before even walking into the operating room. A working knowledge of physics and electronics makes you a better technologist.

This post walks through essential electronic concepts, tying them directly to their roles in the OR.

Atoms and Charge: The Foundation of Electricity

All electronic behavior begins with the atom. Electrons are negatively charged particles orbiting the nucleus. They can move freely between atoms, which is the essence of current flow. Protons are positively charged and reside in the atomic nucleus. Neutrons are neutral and also reside in the nucleus.

While protons and neutrons remain fixed within the nucleus, electrons can move. And when they do, they create electric currents.

Force, Charge, and Electric Fields

The movement of charges is governed by Coulomb’s Law, which describes the electric force between two charged particles:

F = k (q1 * q1) / r^2

For the non-math people: The force increases with greater charge and decreases with greater distance. In IONM, this matters because electric fields drive ionic movement within biological tissues. When we stimulate the nervous system (e.g., via transcranial or peripheral stimulation), we apply an electric field across tissue. This field exerts a force on ions in the extracellular space, causing them to move. This ionic movement constitutes current, which depolarizes neurons and generates action potentials. These action potentials are the very signals we aim to measure.

Voltage: Electrical Potential (and Biological Implications)

Voltage, or electric potential, is a form of potential energy per unit of charge:

Voltage = Energy transferred / Charge

V = E/Q

In neurophysiology, we observe voltage changes when action potentials propagate or when populations of neurons fire in response to stimulation. Increasing voltage is a key component of supramaximal stimulation. We often use scalp electrodes to record these evoked potentials, and the recorded voltage amplitude is influenced by distance from the neural generator and electrode orientation.

Current and Resistance

Current (I) is the flow of electric charge through a conductor, measured in amperes (A). One ampere corresponds to one Coulomb (C) flowing through a conductor in one second. Resistance is the opposition to direct current (DC) flow, measured in Ohms (Ω).

Their relationship is defined by Ohm’s Law:

V=IR

In practical IONM terms, adequate electrode-skin contact minimizes resistance. Poor contact or dry skin increases resistance and adds noise to recordings. Current plays a key role in stimulation and recording of biological (not just neural!) signals as well.

Capacitance: Storing Charge and Filtering Signals

A capacitor stores charge across two conductive plates separated by an insulator.

- Unit: Farad (Coulomb/Volt)

- Capacitors charge and discharge according to the time constant (τ = RC).

This time constant affects how capacitors respond to changing (AC) signals which is a key concept in frequency filtering.

- Low-frequency signals (longer periods) charge the capacitor more fully.

- High-frequency signals (shorter periods) are attenuated because the capacitor doesn’t have time to fully charge/discharge.

This forms the basis for high-cut filters in recording equipment, which reduce high-frequency noise, such as electrical interference from equipment (e.g., cautery, warming devices). Low-cut filters are used to reduce low-frequency noise in our recordings. They work by allowing frequencies above a certain threshold to pass through while attenuating those below it. The cutoff frequency is defined by the point where signal amplitude falls to 70% of its original value (the -3dB or half-power point).

Low-cut filters can be built using a capacitor in series with the signal and a resistor to ground. When low-frequency signals pass through this setup, the capacitor acts as a block, since at low frequencies capacitors don’t charge and discharge fast enough to pass current efficiently. But at higher frequencies, the capacitor can respond quickly, allowing the signal to move through the circuit.

A poorly adjusted low-cut filter can mask or distort slower signals, like long-latency cortical responses. So, while we use them to reduce noise, care must be taken to set the cutoff appropriately. Not too high, or you might filter out the very potentials you’re trying to record.

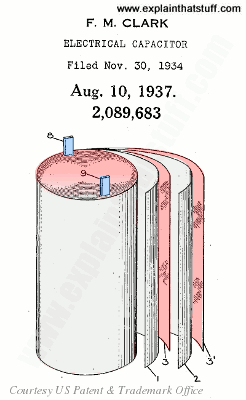

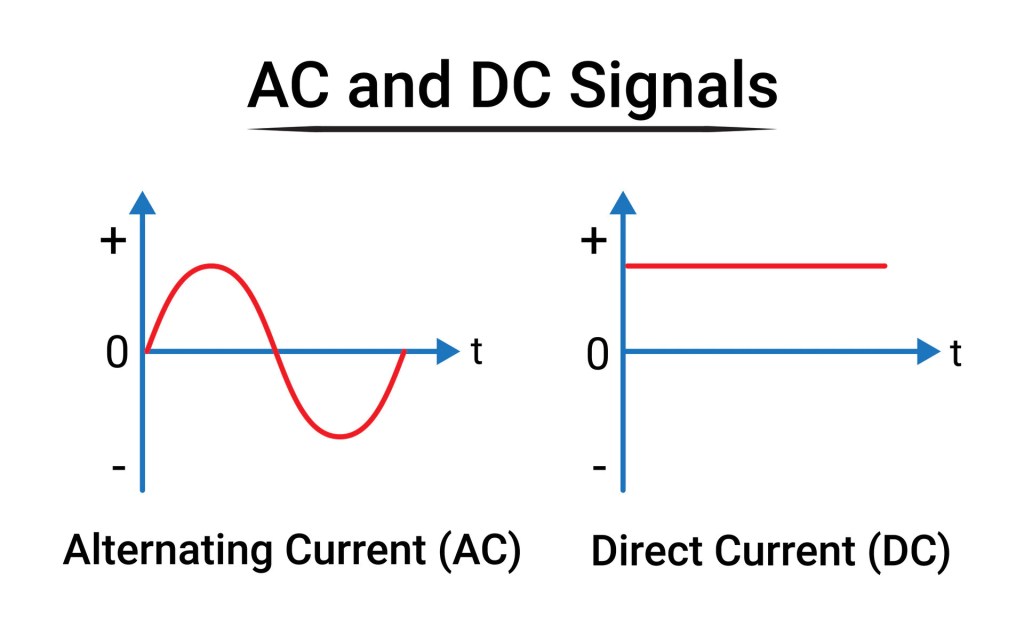

Impedance: Alternating Current Resistance

Direct current (DC) is an electric charge that flows consistently in a single direction, unlike alternating current which reverses periodically. In DC circuits, the voltage is constant, meaning the electrical potential difference does not vary with time. This type of current is commonly stored in and supplied by batteries, fuel cells, and solar panels. While DC is not typically used for long-distance power transmission due to greater energy loss and conversion limitations, it is essential for many low-voltage applications such as electronics, electric vehicles, and some types of medical and monitoring equipment. In the context of intraoperative neurophysiology and other biomedical applications, DC is usually avoided in stimulation protocols because it can cause tissue damage due to electrochemical buildup at the electrode-tissue interface.

Alternating current (AC) is an electric current that changes direction periodically – typically at a frequency of 60 Hz (cycles per second) in North America and 50 Hz in many other parts of the world. AC is the standard form of electricity used in homes, offices, and industrial settings. One of its major advantages over DC is that it can be easily transformed to different voltages using transformers, making it highly efficient for long-distance power transmission via the electrical grid. The sinusoidal nature of AC allows for easier generation and distribution, and it interacts with capacitive and inductive elements in circuits, leading to considerations like impedance and phase shifts. In medical applications, including neuromonitoring, the presence of ambient AC power (e.g., 60 Hz noise) is a common source of electrical interference and must often be filtered out from bioelectric signals.

Impedance (Z) is the total opposition that a circuit presents to the flow of alternating current. It is a complex quantity, measured in ohms (Ω), and encompasses both resistance (the opposition to current flow due to resistive elements like wires and resistors) and reactance (the frequency-dependent opposition caused by capacitors and inductors).

In other words, impedance takes into account not only how much a material resists current flow, but also how it stores and releases energy in the form of electric and magnetic fields. This concept is particularly important in AC circuits and in systems that handle signals with varying frequencies, such as EEG, EMG, and other neurophysiological recordings. In intraoperative neuromonitoring, impedance measurements are used to verify good electrode contact with tissue: Too high an impedance may indicate poor electrode placement, drying, or open circuits, while too low may suggest shorting or bridging between electrodes.

Electrode impedance should be kept below 2500 ohms to reduce noise and ensure high-fidelity signal recording. We measure this before and sometimes during surgery to maintain recording quality. Always check your impedance before beginning monitoring to ensure electrodes are secure and plugged in!

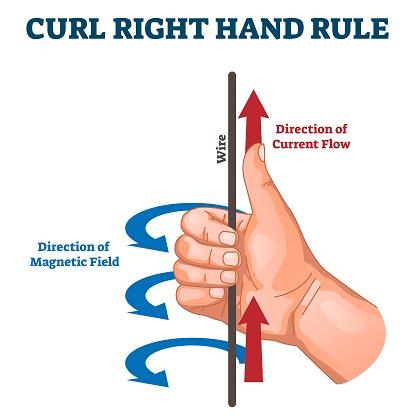

Inductance and Electromagnetic Interference

Two fundamental rules of electromagnetism matter here:

- 1) A current-carrying wire creates a magnetic field perpendicular to the current (Right-Hand Rule).

- 2) A changing magnetic field induces a new current in nearby conductors.

In the OR, this means that any electrical device – especially those running at 60 Hz – can generate electromagnetic noise. This includes cautery units, fluid warmers, and surgical microscopes.

To mitigate this:

- 1) Distance is your best friend. Move cables and electrodes away from power sources.

- 2) Orientation matters. Rotating a device may reduce the strength of its EM field hitting your leads. Lowering the device, if possible, can help as well.

- 3) Cable shielding and twisting lead wires can help reject common-mode interference. Don’t let your cables become frayed – Replace them if they do!

Electronics Matter in IONM

Understanding basic electronics empowers IONM professionals to optimize signal quality, troubleshoot noise, protect patients from electrical risks, and communicate effectively with surgical and anesthesia teams about interference sources. You may have complete mastery of neuroanatomy, but do not skip over the essentials of basic electrical components and electrical theory!